On Derivative Desires

Everything I have ever thought and desired has already been desired before - with companions Deleuze and Guattari, Richard Dollimore, Maurice Blanchot and Francois Reichenbach.

There are moments in my reading and academic education where I have had the feeling that I am thinking a truly radical new thought that has never been thought before. All of these I have found to be false prophets. When I started reading Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus last year, I found myself disappointed. I found that so many of the writers who had truly captured something of my conceptual curiosity, had been so radically influenced by the work that I had accumulated this expansive secondary articulation of ideas, when I may as well have read the book years ago. When I lament about the familiarity of Anti-Oedipus, a friend tells me that I ought to count my blessings. Perhaps what it reveals is that when I read I am able to activate this secondary critical capacity which reveals some of the source material. She also reminds me that to diminish the literature I read to derivative, is to do a disservice to the function of literature and art.

Even before I encountered D&G, most of my writing has been about desire. This desire takes many forms: from sexual desire and its revelations, the concept of ambition under capitalist regimes of individuality, and the one that most troubles me: how can we give our liberatory desire the agency to act. I read a lot of auto-theory. I write a lot of auto-theory. I am in equal measure repulsed by the genre’s individualised self obsession, its inability to escape the cage of the authors own self-hood. At the same time, when I am trying to make sense of dense theoretical texts on regimes of representation and capitalism - whatever the body without organs is - I find myself impulsively attempting to entangle my reading with embodied lived experience. This, I think, is the form at its best: when it allows for the elaboration of complex ideas through processes of anecdote and example.

I picked up Richard Dollimore’s Desire: A Memoir in my old university library because the title caught my eye. It touched me right away. Something about the author's ability to speak so plainly about shame, to oscillate between critical theory and personal experience with a lightness of touch. Something else too - some commonality of voice. This is one of the clichéd joys of literature: the feeling of communion when you discover another person has experienced the same feelings that you thought were unique. I wonder what my affinity is to the work of homosexual men. Perhaps some commonality in queer longing and repression, an almost pathological impulse to intellectualise my own desire -

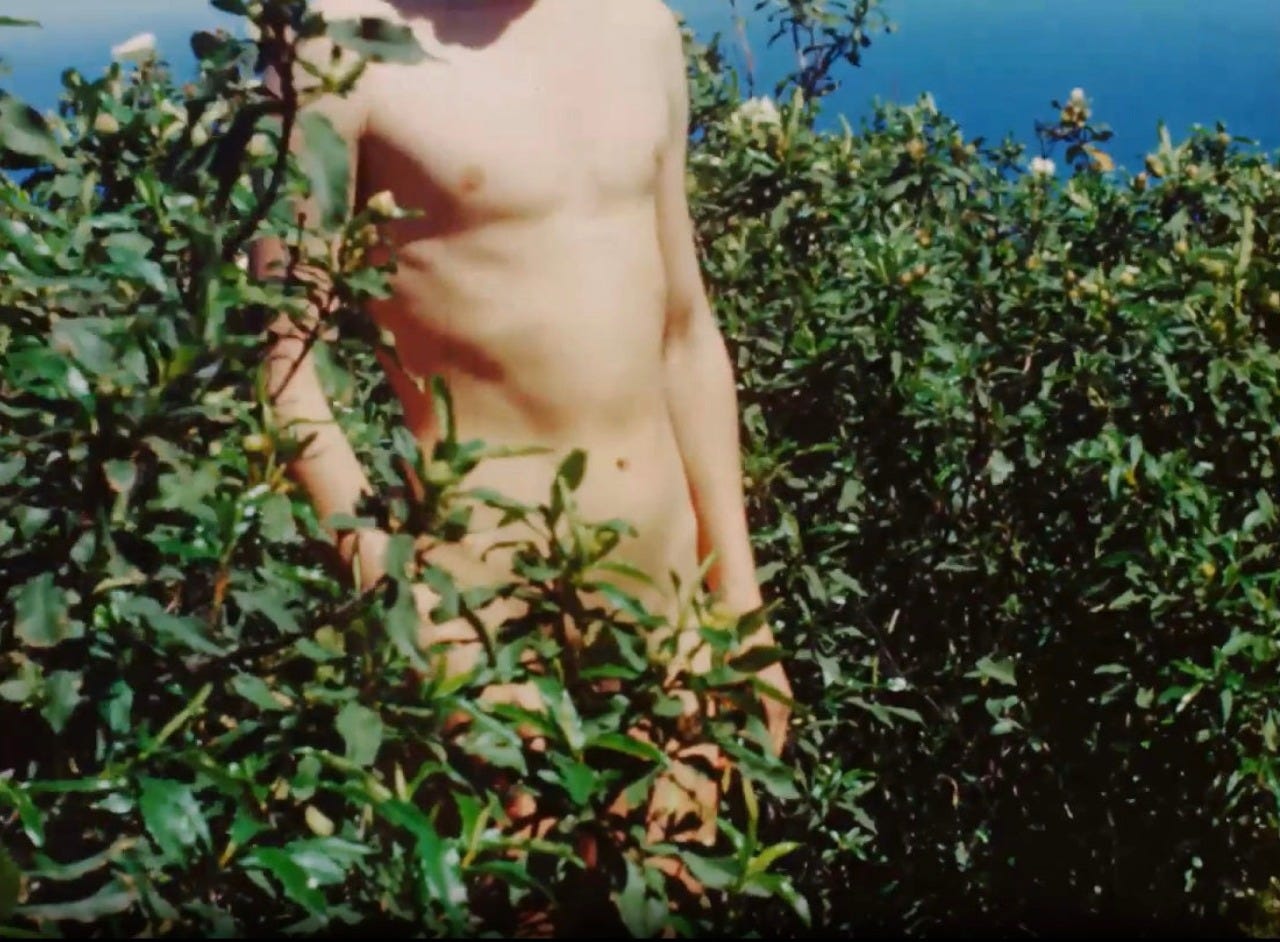

There is a film I watched recently called Nus Masculins, by the director François Reichenbach. Filmed in 1950, it is 40 minutes long, silent and shot entirely on 16mm. It is sometimes called a travel diary, sometimes a series of portraits. In fact, one could call it a love letter to masculinity. In the film a series of voiceless, beautiful men, pose for the camera. Here, a man leans against a statue forming another figure in a row of men carved from stone. A different man tucks one leg up to his stomach, painterly against a mass of rock. Here a man in a white shirt reclines in a field of yellow flowers. Here a group of men flamboyantly parade through Central Park, their gestures and gait unmistakably camp. Here, the pale torso of a man weaves his way through green foliage against a backdrop of startling blue water. The camera traces his neck, his tight stomach, down to his flaccid cock. I am touched by something in the film, perhaps the impeccable cinematography, perhaps the intimate vulnerability which plays out between auteur and subject, perhaps the freedom of seeing openly gay men joyously happy in a pastoral past. The subject’s muteness renders the men's bodies objectified and the camera moves lovingly across their bodies and faces. We are left to wonder how many of these were Reichenbach’s lovers, how many were friends. The film is indisputably homoerotic, charged with the directors non-normative desire.

The film was missing, presumed lost for decades, and as far as I can tell since its rediscovery it has had only one public outing, (with the exception of the two clips which I played last week at the BFI). I am interested in its depiction of easy homosexual desire at a time which we associate with secrecy and violence - how else has gay desire been written out of our public consciousness? Not gay shame, gay violence, gay suffering - I mean the love of men - devotion to the body of another. The objectifying function of the camera here makes way for a form of representation which frees us from the shackles of the narrative construction of queer desire.

Dollimore writes about the obliterating force of same-sex desire, the capacity it has to instigate a complete unravelling of one's sense of boundaries, time and selfhood. Now this all might strike you as really rather cerebral, but the truth is that my experience of romantic and sexual desire has always felt to me confusing, obliterating and intellectual. This imposes no moralising judgement - call it ego-death, call it transcendental, call it a mental health crisis - the unravelling of self is nothing if not transformative. Dollimore’s capacity to instantiate the complexity of desire, specifically how it interferes with one's own sense of self-hood, felt at times like a generous second hand reading of Deleuze and Guattari. He writes “If I experience myself at all, it is as something contingent and provisional, held together primarily by a shifting, conflicted consciousness, which doesn’t feel that interesting in and of itself. More exactly, for me the individual life, including my own, is of interest mainly to the extent that it resonates with life in the larger senses of the word, the life which passes through it. That's also true of the life of desire. When I started reading philosophy and literature, I soon realised that whatever we are thinking and desiring as individuals has been thought and desired before.”

Reading Anti-Oedipus, it is a text intimately concerned with flows, production and consumption, intimately bound together, consummated in their very becoming. It is not about the production of objects, rather in fragmenting them, which is itself an attempt to elicit a new kind of representation. It is attentive to the production of effects, and as such the form and content collide in self-referential realisation: how a particular kind of writing spontaneously produces post-textual effects, which are about the what and how of writing. In other words, they write in order for what they say to be experienced within the way they say it. The opacity of their metaphors are themselves attempts to instigate forms of knowing and becoming which reach beyond the content of the text and fold the ideas and form into a process in which neither one is inside or outside the other: call it symbiosis, or call it flow. D&G write, “Desire causes current to flow, itself flows in turn and breaks the flow.”

Maurice Blanchot’s Awaiting Oblivion, similarly, I discovered on the shelves of my old university library. It was a slim volume, filed under ‘french literature” and in a section I had come to learn was my natural home, a sort of interdisciplinary playground between classic theory and its derivatives. I liked its enigmatic tone, the ambiguity between the two protagonists. As I read it I always imagined it as a series of cinematic shots: I imagined it set in white hotel room, startlingly nondescript. The woman and the man would be both aged, but not old, marked by time, but not yet riddled with nostalgia. She would sit and he would pace. At times she would sleep and she would be beautiful but sex-less. He would be at best troubled, and at worst altruistic. They would be intimate, and at once in constant friction. The density of the text and its concern with the subtleties of communication, how complex the slightest gesture or phrase can be between two people fascinated and frustrated me. Nothing happens: they come to no conclusions. As the pages draw on, we are left only with a greater sense of emptiness, which not even the tight and precise language can assuage. How can people speak for hours and say nothing at all?

Re-reading the opening passage of Anti-Oedipus, I discover that Blanchot directly influenced D&G and I am shocked to find the derivation of the text which I had iconised as the only new form of thinking. Maybe something does not come from nothing, after all. Blanchot writes, “They both searched for a poverty in language. On this point they agreed. For her there were always too many words and one word too many, as well as overly rich words which spoke excessively. Although she was apparently not very learned, she always seemed to prefer abstract words which evoked nothing. Wasn’t she trying, and he along with her, to create for herself at the heart of the story a shelter so as to protect herself from something that the story helped attract?”

Dollimore writes, “the primordial first desire is the death of desire itself”. He is talking not of the death drive, but rather the lingering desire for a time before need itself, before there was a self to need. Think of the baby’s first gasping breath and with it, the child's wail. For what? Food, water, warmth, the care of another. From our first breath we come into the world as squirming needy creatures, wounded by desire.

In my journal I had already written, “My desire for the death of desire: sex and satiation.”