[moaning]

On Polly Bartons 'Porn: An Oral History', addressivity and trying to get ChatGPT to do my writing for me.

Polly Barton: “Do you understand the potential for humiliation in this conversation with me?”

Cherry blossom in the rain. He tells me to fuck him exactly like that, his hands held down. I go to the dentist and they tell me to floss more. He spits into my mouth. The black hairs on his collarbone are wet and twisted where my teeth met his skin. I cycle home through Peckham in the dark and feel that perfect concurrence between sound and image. A cinematic moment - you know the type.

“Perhaps it is becoming clearer why I felt no romance when you told me that you carried my last letter with you everywhere you went for months on end, unopened. This may have served some purpose for you, but whatever it was surely it bore no resemblance to mine. I never aimed to give you a talisman, an empty vessel to flood with whatever longing, dread, or sorrow happened to be the days mood. I wrote it because I had something to say to you.”

In ‘Porn: An Oral History’ by Polly Barton, she interviews 19 friends and acquaintances about their porn habits, their private sexualities and desires. What astounded me most was not the content itself, but its addressivity - the mode by which conversations unfold. The interview form is loose, casual. It lacks rigour. It resists academic structure, and precisely for that reason, becomes a delicate examination of conversation itself: the hesitations, the awkwardness, the pauses that mark how shame shapes language.

At one point, Barton reflects: “With porn, and with sex to a certain extent, talking about it has been regarded as shameful for so long that it has almost become discredited as a form of discourse.” We lack, in many ways, a vocabulary for our own desires. To take our sexualities seriously would mean to confront the pleasure—and sometimes the inevitability—of power imbalances. To acknowledge motivation, want, arousal. It’s possible to be critical of our desires without retreating into academic distance, without masking the reality of sex and masturbation behind theory.

When we talk about porn, it often falls into one of two categories: the joke or the critique. Either it’s something seedy and shameful, a punchline. Or it’s a wholesale assault on feminism—porn as aestheticized domination. Both modes fail to ask what porn actually is, how it functions, and how absolutely ubiquitous it is.

Suddenly we realise there is blood everywhere. It on his sheets. It’s dripping from his erect penis. There’s blood all over my hands. It drips thickly and brightly; as though its crimson blush will stain.

He and I talk about Spinoza and he tells me about the misattribution of arousal. A study: subjects cross either a shallow creek or a deep ravine, then meet an attractive woman who gives them her number. Those who experienced fear—the adrenaline of the ravine—were more likely to call her. The quickening pulse, the proximity to danger. Arousal isn’t a misinterpretation; it’s real. But the attribution—what we assign it to—is slippery. Maybe that’s the heart of it: desire as a process of affect, a misread pulse, a projected wanting.

I come back from work late and hungry. He watches me eat in the low light of his kitchen. Cooking is his way of caring. But it also marks something else—a turning point in my own unwieldy appetite.

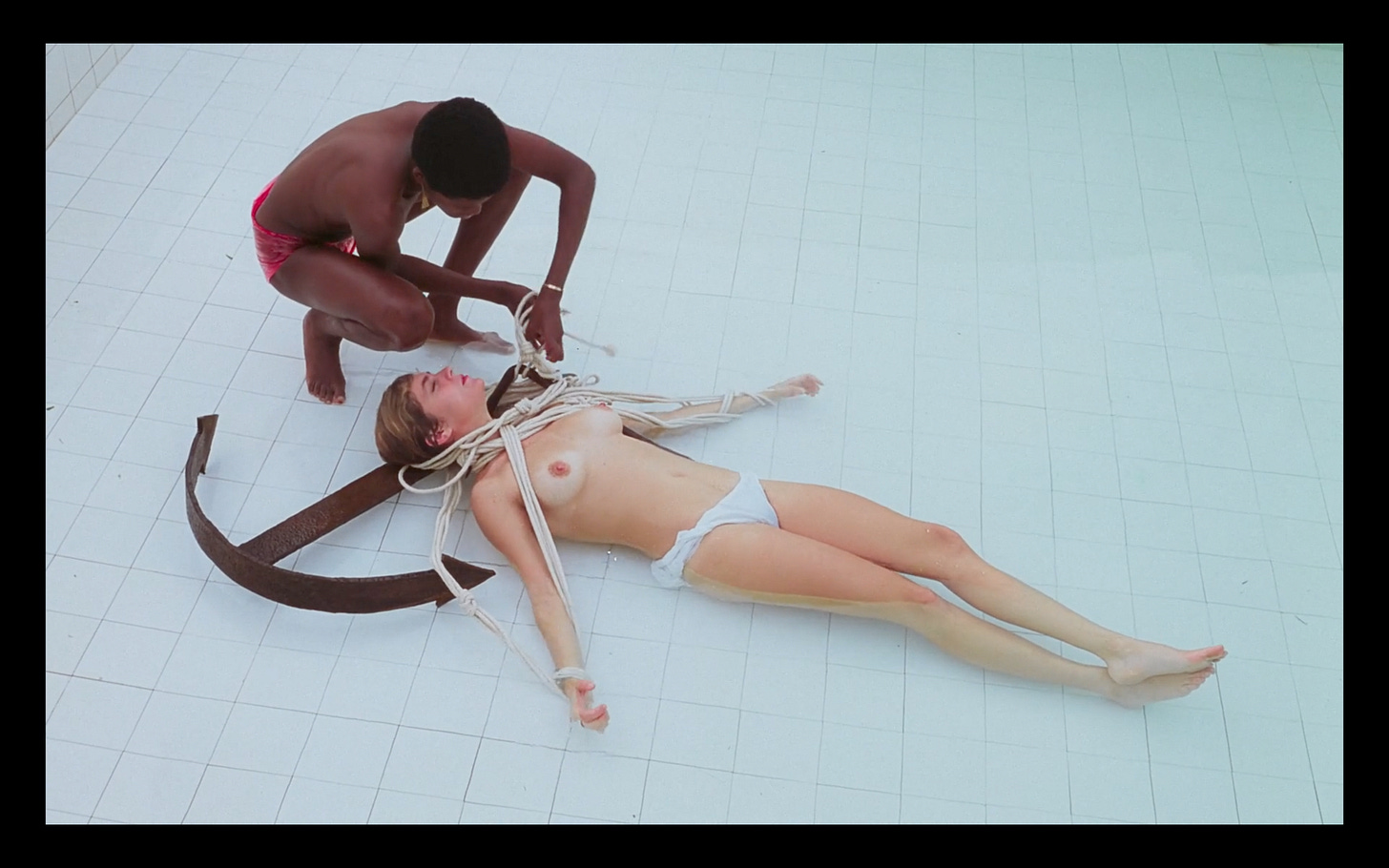

In the Brazilian film Onda Nova, it is the firmness of the actors bodies which stands out to me. The country’s first women’s football team comes together and splinters apart. Sexuality is folded into ambition. The girls fuck, fight, smoke, drive too fast, yell at their mothers. And then: the film’s climax is a rupture of masculinity—two men having sex. The orgasm, the gunshot. A metaphor, maybe. Maybe not.

I tell him about the film while we are lying in the summer sun - thinking of girls in their little short shorts and his skin against mine. And perhaps there was a kind of a seriousness which existed in the space between us- even when it was laughter, even when it was light. I often wondered about its minutae. I look at him and he hesitates, his eyes flick towards me and away. I am taken aback when he looks at me directly. So much so that he witnesses the smallest of recoil flicker across my face and, as such, he averts his gaze. All of this happens in a second. Yet it contains a world: how we react to one another. I want to take responsibility for the way in which we respond, the ways in which we are responded to. I’m attentive to the address of the story.

Earlier in the year, my flatmate held a photography show which included intimate moments from her life: pictures of her father, of her breakfast, of her friends, of the cat which stalks our garden - but more than anything, she photographed past lovers. There was a photograph in the show which I tasked my friends with finding - an inappropriate easter egg hunt. Once found, it’s almost disappointing. Flacid and sheathed in a used condom, the body is beheaded and anonymised by the frame of the camera. Penis, dick, cock: I was rather incised by this reclamation of her desire.

I ask the dreaded Chat GPT to write me a piece of autotheory. It writes:

It started when I began watching porn with the captions on. Not subtitles—actual captions, the kind made for deaf viewers: [moaning], [wet sounds], [man grunting], [bed creaking]. Something about the clinical exactness of it fascinated me. Desire reduced to an aural taxonomy. An archive of groans. It was comforting, in a way. Like I could finally locate sex within a system of signs.

I accidentally leave my journal out and open on my bed when he arrives and collapses onto my covers. Shame rises in my throat, as I fear the things he could have read: confessions of desire, heartbreak, inexperience, infidelity. He closes his tired eyes.

Chat GPT continues:

I remember lying in bed with a new lover and him saying, “You’re really hard to read.”

I wanted to say, “Yes, and you’re reading me wrong.”

But instead I smiled, as if to say: please, try harder.

The address of AI fails to make emotional contact. Its formula knows the right phrases to say, it understands how to structure a sentence with staccato, to interweave anecdotes with cultural capital - the interjection of the image-world. The failure of its address relives me. Its writing is like the letter unopened: a gesture which has reference only to itself.

The captions continue: [woman gasps], [man sighs], [skin slapping].

Barton writes: “I think people have a responsibility towards their desires.”

What shocked me most upon reading her book were the confessions of so-called progressive men and women, who in the comfort of their own private fantasies, are aroused by the very systems of domination and subjugation which they claim to denounce.

He tucks a pink blossom behind my ear. He tells me about his indebtedness to his friends and I laugh, how very David Graeber. He leaves me asleep in his bed and I wave goodbye to his flatmates rather than creeping out the door. I cook steak in a red wine and raspberry sauce. Serve with garlic roasted potatoes and tender stem broccoli in the candlelight of my wooden basement kitchen. I even go in for seconds. I think he looks fantastic: his brown skin against the blue of my bed. A photographic moment - you know the type.

Arousal flickers across his face with an expression which resembles alarm or surprise. I tell him, for all of my feminist education, sometimes I just want to be told what to do.